If you’ve lived in Baja long enough, you’ve heard about the Rosarito desalination plant the way you’ve heard about flying …

If you’ve lived in Baja long enough, you’ve heard about the Rosarito desalination plant the way you’ve heard about flying …

If you discovered the water outage standing in your bathroom, shampoo already in your hair, you were not alone. Across …

Problem Solved – Part 2 WW Editorial Read “Part 1: Baja Faces Water Cuts” here… Wilderness is not a luxury …

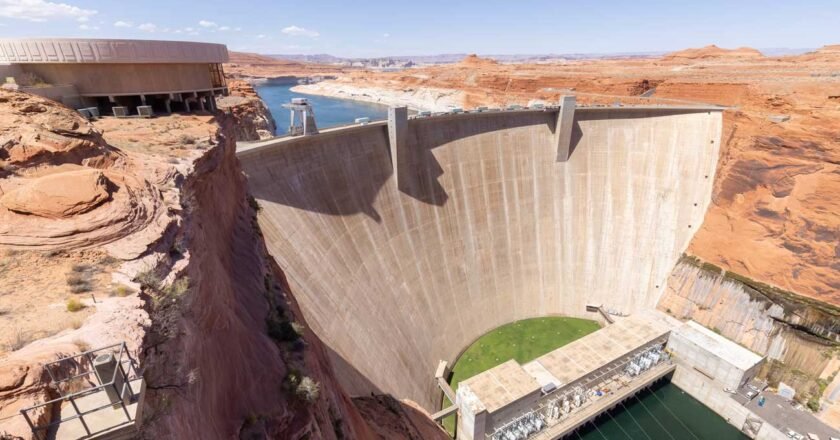

High-stake Negotiations Faulter Water Watch Editorial, Part 1 Time is running out for Baja and the seven states that are …

Water Watch Editorial Lake Mead is dropping again and this is a reminder that we are fast approaching 2026. Freelance …

Just a short drive south of Rosarito and 35 kilometers north of Ensenada, tucked between the waves of the Pacific …

The numbers are grim—46 lives lost in Baja California this year to heat-related causes, with nearly 250 others suffering serious …

Rosarito’s most heartwarming tradition is making its way back to shore. After weeks of uncertainty, the beloved surf therapy sessions …

How Baja plans to stay hydrated If you’ve been following our ongoing coverage of the 1944 Water Treaty, here’s your …

Sheinbaum responded diplomatically Donald Trump sent flowers on X—digitally, of course. He called President Claudia Sheinbaum “a magnificent president” and …